Specializing in fieldwork and strategic planning, I help professionals build skills in collaboration, communication and documentation within their communities. ArtVillage offers professional development programs and public programs that feature the healing potential of folk arts and oral history. For psychologists, teachers, social service specialists, health care providers, tourism industry leaders, and other professionals, these programs inspire wonder, create connections, and encourage caring.

Through ArtVillage, I am proud to showcase the folk and traditional culture of Western New York. For over a decade, I have offered my services as an independent folklorist across the region. Working with three non-profit organizations to advance the study and appreciation of folklore, I am dedicated to working with and promoting the talents and lessons of traditional artists.

Through ArtVillage, I present high quality workshops, exhibits, and public events for organizations, galleries, museums, and schools. ArtVillage folk arts programs help professionals and the people they serve increase their understanding and enjoyment of culture and history, as well as expand audience capacity and mission fulfillment.

all photos and articles by Valerie Walawender, M.A. Why are folk and traditional arts important to you and your organization?

Why are folk and traditional arts important to you and your organization?

Traditional arts and folk arts are part of a broad category known as folklore. In commenting on folklore, Benjamin A. Botkin offered, “Every group bound together by common interests and purposes, whether educated or uneducated, rural or urban, possesses a body of traditions which may be called its folklore. Into these traditions enter many elements, individual, popular, and even “literary,” but all are absorbed and assimilated through repetition and variation into a pattern which has value and continuity for the group as a whole.”

The power of the arts to transform lives is especially exciting in the practice of folk traditions. Practices that reach back hundreds and even thousands of years lend a sense of continuity across generations. They also help to build a sense of family within the community. Many artists pass on their art forms to their children and grandchildren, nieces, nephews and friends.

Storytelling, relationship and the creation of art are key healing elements of folklore. Folk arts can offer the individual opportunities for passing on tales, rhythmic small and large motor coordination, visual and auditory stimulation, symbolism, and intergenerational oral tradition and practices. These activities affect the processing and flow of emotional energy and contribute to individual mental health. Daniel Siegel, author of The Developing Mind, explains that since stories are created within a social context, the process of storytelling or narrative is inherently social. He states that children who have been affected by early trauma can be helped to heal through storytelling activities. Folk and traditional arts are a way people can share their experiences. Folk and traditional arts can increase vitality, creative energy, ideas, and personal expression.

Storytelling, relationship and the creation of art are key healing elements of folklore. Folk arts can offer the individual opportunities for passing on tales, rhythmic small and large motor coordination, visual and auditory stimulation, symbolism, and intergenerational oral tradition and practices. These activities affect the processing and flow of emotional energy and contribute to individual mental health. Daniel Siegel, author of The Developing Mind, explains that since stories are created within a social context, the process of storytelling or narrative is inherently social. He states that children who have been affected by early trauma can be helped to heal through storytelling activities. Folk and traditional arts are a way people can share their experiences. Folk and traditional arts can increase vitality, creative energy, ideas, and personal expression.

In traditional arts, the process of storytelling happens within a family or community context. Thus, social, sensory, and psychological aspects are intertwined in a single process. When an individual is affected by extreme stress or trauma, they may have less ability to regulate their own emotions, focus, think, and problem solve. The arts, folk arts and folklore can actually help people think and function better emotionally and cognitively.

In traditional arts, the process of storytelling happens within a family or community context. Thus, social, sensory, and psychological aspects are intertwined in a single process. When an individual is affected by extreme stress or trauma, they may have less ability to regulate their own emotions, focus, think, and problem solve. The arts, folk arts and folklore can actually help people think and function better emotionally and cognitively.

Whether the folk or traditional art is the or Native American corn husk doll making Puerto Rican aguinaldos, Polish pisanki, African American Gospel singing, a story is being told and transmitted. The story is not just about the technical details and skills entailed in the practice of the art form. Cultural, family, and individual values are passed on. Tradition, history, symbolism and lore are rich in meaning on a multitude of levels. The whole brain is used in this creative activity. A heightened sense of self, an enhanced sense of identity, and meaningful memories are made.

Whether the folk or traditional art is the or Native American corn husk doll making Puerto Rican aguinaldos, Polish pisanki, African American Gospel singing, a story is being told and transmitted. The story is not just about the technical details and skills entailed in the practice of the art form. Cultural, family, and individual values are passed on. Tradition, history, symbolism and lore are rich in meaning on a multitude of levels. The whole brain is used in this creative activity. A heightened sense of self, an enhanced sense of identity, and meaningful memories are made.

According to the American Folklife Center, folklore can be collected from almost anyone. However tradition bearers – certain people “by virtue of their good memories, long lives, performance skills or particular roles within a community” may be especially adept or identified by others as being able to transmit the information and “lore” sought by others.

Individuals may gain an increased appreciation of the tradition bearers in their own family or community – parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, traditional craftspeople, shopkeepers, musicians, and others who transmit the traditional stories, lessons and skills that would otherwise remain hidden or unexpressed.

Traditional arts and well being

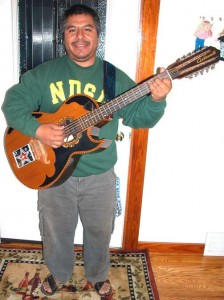

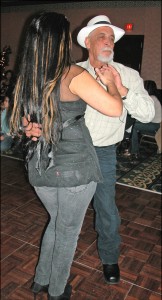

Art forms, whether dance, song, stories or crafts, are often used as vehicles for families and community to come together, and pass down family lore.

Art forms, whether dance, song, stories or crafts, are often used as vehicles for families and community to come together, and pass down family lore.

Participating in the arts is good, not only for intergenerational community building and family relationships, but the actual health of the brain. Especially when shared in caring community contexts, these arts are also known to contribute to well-being and continuity of the family. For instance, Native American storytelling, provides moral lessons in amusing or intriguing tales that entertain and bond both young and old.

The Puerto Rican Aguinaldos (caroling) tradition, brings children, teens, parents, aunts, uncles, grandparents, friends and neighbors together in a joint celebration where everyone has a creative part to play.

African American Gospel singing has some of its roots in the field songs and spirituals sung by slave laborers on the plantations. They inform the younger generation not only of their relationship with God, but with triumph over their heart-wrenching history.

Folk and traditional artists often act as a foundation for the community. They lend continuity and a rhythm of life across generations, decades and even centuries. The potential for these tradition bearers to grow in their role as community leaders is something to ponder. As transmitters of culture, the practices of folk artists and other tradition bearers can be utilized in the prevention of child abuse and child neglect; strengthening the family; and building identity and unity within the community. By knowing their roots, people can discover their long forgotten history, understand better who they are today, and have a more solid basis for who they are to become tomorrow.

Folk and traditional artists often act as a foundation for the community. They lend continuity and a rhythm of life across generations, decades and even centuries. The potential for these tradition bearers to grow in their role as community leaders is something to ponder. As transmitters of culture, the practices of folk artists and other tradition bearers can be utilized in the prevention of child abuse and child neglect; strengthening the family; and building identity and unity within the community. By knowing their roots, people can discover their long forgotten history, understand better who they are today, and have a more solid basis for who they are to become tomorrow.

Organizations can become stronger and better serve their customers when they not only understand, but share in the celebration of folk traditions on deeper levels than the commercial consumer offerings geared to a mass market. For instance, most American’s exposure to the Mexican Day of the Dead celebration is limited to some reference to a gaily dressed skeleton dangling on a piece of elastic. However, the actual Day of the Dead celebration is an exquisite, three to four day period of connecting with their family, both alive and deceased, in a spirit of joyous reverence and home-coming. (See Mexican traditions) The celebration is cause for reflection on life and death, and the mystery that lies beyond.

How did I get interested in folk and traditional art?

As first-generation Americans, my parents passed on the practices, traditions and stories of their parents to me and my siblings. My mother’s father was born in Sweden and her mother’s parents were from Alcase Lorraine, at the border of France and Germany. My paternal grandparents were both born in Poland. Our family celebrated Wigilia, the Polish Christmas Eve feast featuring the sharing of the oplatek, the Christmas wafer. My Polish grandmother always had pisanki, “written eggs” on display during the Easter holiday, and we had our baskets, Swienconka, blessed at church on Holy Saturday. My mother passed on her Swedish heritage to us, as we celebrated Santa Lucia Day in December, and always had on hand, a supply of Swedish Dala, traditional carved wooden horses.

My parents told lively stories about when they were dating, and attended tent meetings with African American gospel singing. My own elementary school experiences included African American and Puerto Rican school mates who celebrated their traditions differently than my family.

As I grew older, I became very interested in different cultures and their traditional art forms. I realized that the knowledge of my own cultural heritage was being lost. I investigated some of our own traditions and found that they went back centuries, handed down by oral tradition from one generation to the next. Along with the traditions, were beautiful lessons and beliefs that were woven into our lives, almost invisibly, yet contributing to the fabric of our lives.

As I grew older, I became very interested in different cultures and their traditional art forms. I realized that the knowledge of my own cultural heritage was being lost. I investigated some of our own traditions and found that they went back centuries, handed down by oral tradition from one generation to the next. Along with the traditions, were beautiful lessons and beliefs that were woven into our lives, almost invisibly, yet contributing to the fabric of our lives.

I grew in my appreciation of all cultures, and began to understand how important folk art, story telling, and traditional practices are for all individuals and families to have a sense of continuity and strength. Also, there is so much to learn from the traditions and practices of different peoples.

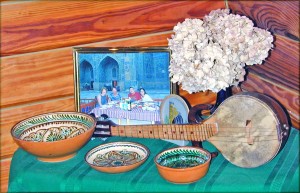

As far back as 1994, as an organizer of a local First Night, (a non-alcoholic New Year’s Eve celebration), I approached a multitude of local persons about displaying and demonstrating their folk art skills at our annual event. Over two dozen traditions were represented, including Lebanese, Syrian, Seneca Indian, Irish, Italian, and German traditions.

As far back as 1994, as an organizer of a local First Night, (a non-alcoholic New Year’s Eve celebration), I approached a multitude of local persons about displaying and demonstrating their folk art skills at our annual event. Over two dozen traditions were represented, including Lebanese, Syrian, Seneca Indian, Irish, Italian, and German traditions.

Years later, as Executive Director of Adams Art Gallery, I began incorporating folk and traditional arts into our annual programming. I invited artists from Eastern Indian, Iranian, Amish, Puerto Rican, Native American and other traditions to exhibit and present public talks on their traditional art.

In 2005, I approached an area museum about developing a folk arts program. I sought out various practitioners of folk and traditional arts in the community, and found one of the great hidden treasures of the area. Hundreds of individuals were carrying on exquisite traditions and intriguing practices that they had learned from their parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles and community. The program grew in scope and popularity, receiving grants and accolades across New York State.

In 2005, I approached an area museum about developing a folk arts program. I sought out various practitioners of folk and traditional arts in the community, and found one of the great hidden treasures of the area. Hundreds of individuals were carrying on exquisite traditions and intriguing practices that they had learned from their parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles and community. The program grew in scope and popularity, receiving grants and accolades across New York State.

I was awarded a scholarship to attend a class and folk arts residency presented by Empire State College and the New York State Folklore Society.

As I was growing in my education about various cultural traditions, I wanted to learn more about traditional Polish folk arts, which I been originally learned from my paternal grandmother. Through the Dunkirk Historical Society, I received a New York State Council on the arts apprenticehip award to study with Master Polish-American folk artist, the Rev. Czeslaw Krysa. In this apprenticeship, I grew in understanding of my own heritage, learning more skill and lore about the art of Pisanki.

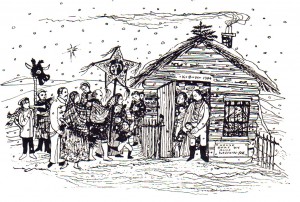

Then in 2011, the Castellani Art Museum of Niagara University invited me to act as Guest Curator of Folk Arts. I was honored during this tenure to research and exhibit the folk art of Polish-American artist, Alice Wadowski-Bak. Specializing in Wycinanki, Polish cut-paper art, Bak also documented through exquisite pen and ink drawings and paintings, Polish and Polish-American folk traditions. Ironically, years before this exhibit, I was inspired by one of Bak’s art works, to create a painting depicting my own family’s Wigilia (Polish Christmas Eve feast).

Then in 2011, the Castellani Art Museum of Niagara University invited me to act as Guest Curator of Folk Arts. I was honored during this tenure to research and exhibit the folk art of Polish-American artist, Alice Wadowski-Bak. Specializing in Wycinanki, Polish cut-paper art, Bak also documented through exquisite pen and ink drawings and paintings, Polish and Polish-American folk traditions. Ironically, years before this exhibit, I was inspired by one of Bak’s art works, to create a painting depicting my own family’s Wigilia (Polish Christmas Eve feast).

I am pleased to continue to pass on the traditions of my parents and grandparents with my children, nieces, nephews and the larger community.

References:

Oring, Elliott. “On the Concepts of Folklore.” Folk Groups and Folklore Genres: An Introduction, ed. Elliott Oring (Logan, UT: Utah State UP, 1986) 1-22

Siegel, Daniel J. The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain interact to shape who we are New York, London: The Guilford Press